23. Historic Associations: The FA’s game expands

It later transpired that Chequer was a joke name, for he was actually Morton Peto Betts, who had originally been registered as a Harrow Chequer and only switched to The Wanderers after his team pulled out of the competition. Quality … the first ever goal in an FA Cup Final was scored by a ringer!

In 1864, the FA’s minutes noted that “no business was conducted” in its first year, and by 1866 Cobb Morley wondered whether there was any point continuing as the FA had already “accomplished the object for which it was established.” But writing rules was one thing, another was getting teams to play by them, and in that respect the FA had almost no influence whatsoever. Even the handful of member clubs merely used the rules as a guide and adapted them to their own tastes.

In 1864, the FA’s minutes noted that “no business was conducted” in its first year, and by 1866 Cobb Morley wondered whether there was any point continuing as the FA had already “accomplished the object for which it was established.” But writing rules was one thing, another was getting teams to play by them, and in that respect the FA had almost no influence whatsoever. Even the handful of member clubs merely used the rules as a guide and adapted them to their own tastes.

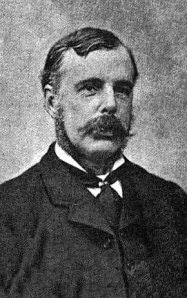

The arrival of Charles William Alcock on the FA committee in 1866 was one of the first catalysts for change. Probably the greatest administrator of 19th century football, he led the shift towards a more proactive attitude. Another factor was the forging of stronger links with the Sheffield FA in the north, described by Morley as “the greatest stronghold of football in England,” and which was already playing games in cities as disperse as  Nottingham, Lincoln, Leeds, Derby and Stoke. The relationship between Sheffield and the FA is often described as one of antagonistic north-south rivalry, but that wasn’t really the case at all. Rather than differences drawing them apart, similarities drew them together, and although they had their differences, they were generally keen to cooperate.

Nottingham, Lincoln, Leeds, Derby and Stoke. The relationship between Sheffield and the FA is often described as one of antagonistic north-south rivalry, but that wasn’t really the case at all. Rather than differences drawing them apart, similarities drew them together, and although they had their differences, they were generally keen to cooperate.

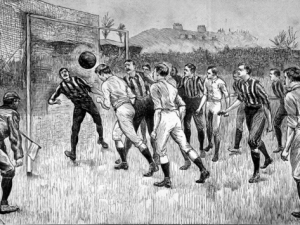

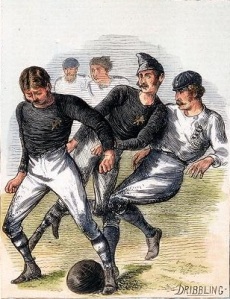

The original FA rules of 1863 had tried to embrace all forms of football, but this proved too difficult and in 1866 the rules were revamped as “the Association decided to throw in its lot with the opponents of Rugby.” The ‘fair catch’ was eliminated, as was the ‘try on goal’, a crossbar was added to the goal, and it was deemed that “a player is not offside provided that he has three opponents between himself and the opponent’s goal,” a rule not unlike the modern-day offside rule, and which opened up the game to allow forward passing. These innovations were clearly influenced by Sheffield, and the two associations finally met in London later that year in the first of what would eventually become a regular tradition of north v south encounters. The two camps still had their differences, the most evident being that in London the ball could be knocked with the hands but not caught, while in Sheffield all handling was illegal and players had learned the crafty trick of heading it instead. London didn’t follow suit until 1870, but made an exception for the player standing nearest to the goal – which was the origin of the unique role of the goalkeeper.

The original FA rules of 1863 had tried to embrace all forms of football, but this proved too difficult and in 1866 the rules were revamped as “the Association decided to throw in its lot with the opponents of Rugby.” The ‘fair catch’ was eliminated, as was the ‘try on goal’, a crossbar was added to the goal, and it was deemed that “a player is not offside provided that he has three opponents between himself and the opponent’s goal,” a rule not unlike the modern-day offside rule, and which opened up the game to allow forward passing. These innovations were clearly influenced by Sheffield, and the two associations finally met in London later that year in the first of what would eventually become a regular tradition of north v south encounters. The two camps still had their differences, the most evident being that in London the ball could be knocked with the hands but not caught, while in Sheffield all handling was illegal and players had learned the crafty trick of heading it instead. London didn’t follow suit until 1870, but made an exception for the player standing nearest to the goal – which was the origin of the unique role of the goalkeeper.

As all games in those days were challenge matches, teams were under no obligation to observe any set code of rules, and rarely did. But this would change when the first cup competitions were organised. In order to enter, teams would need to play by a common rulebook, and this was how soccer came to be standardised around the country. Sheffield led the way here as well, with the Youdan Cup being played in 1867, but it was Charles Alcock’s idea in 1871 to establish the FA Challenge Cup that really set the cogs in motion. Only fifteen teams entered the first edition, with The Wanderers beating the Royal Engineers to win the inaugural title, but the tournament would grow each year and still exists today. Sheffield and Shropshire became the first entrants from the north of England to enter in 1873, and it wasn’t long before there were similar regional cup tournaments being played all over the country. The most important thing is that they were all, more or less, playing by the same rules.

As all games in those days were challenge matches, teams were under no obligation to observe any set code of rules, and rarely did. But this would change when the first cup competitions were organised. In order to enter, teams would need to play by a common rulebook, and this was how soccer came to be standardised around the country. Sheffield led the way here as well, with the Youdan Cup being played in 1867, but it was Charles Alcock’s idea in 1871 to establish the FA Challenge Cup that really set the cogs in motion. Only fifteen teams entered the first edition, with The Wanderers beating the Royal Engineers to win the inaugural title, but the tournament would grow each year and still exists today. Sheffield and Shropshire became the first entrants from the north of England to enter in 1873, and it wasn’t long before there were similar regional cup tournaments being played all over the country. The most important thing is that they were all, more or less, playing by the same rules.

One of the most unlikely entrants of the first ever FA Cup was a team from Glasgow, Queen’s Park, the first real contact between English and Scottish soccer teams. A year earlier, the two nations had played the first ‘international’ in London, but there was outrage in the Scottish press. After Alcock failed to get any response to his invitation for a bona fide team to come down from “north of the Tweed”, his ‘England’ team instead took on eleven Scottish expats living in the capital, some of whom only had very ambiguous links with Scotland. He reissued his challenge to the Scottish football clubs, but was told that he was fighting a lost cause, for “the association rules will find no foemen worthy of their steel in Scotland.” Clubs north of the border preferred the Rugby rules, and instead the 1871 match would be the first ever rugby international.

One of the most unlikely entrants of the first ever FA Cup was a team from Glasgow, Queen’s Park, the first real contact between English and Scottish soccer teams. A year earlier, the two nations had played the first ‘international’ in London, but there was outrage in the Scottish press. After Alcock failed to get any response to his invitation for a bona fide team to come down from “north of the Tweed”, his ‘England’ team instead took on eleven Scottish expats living in the capital, some of whom only had very ambiguous links with Scotland. He reissued his challenge to the Scottish football clubs, but was told that he was fighting a lost cause, for “the association rules will find no foemen worthy of their steel in Scotland.” Clubs north of the border preferred the Rugby rules, and instead the 1871 match would be the first ever rugby international.

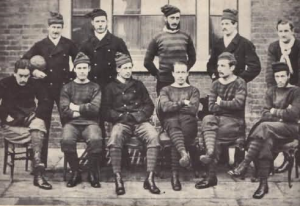

Formed in 1867, Queen’s Park was a rare exception. Unimpressed by rugby, they played the Association game, and had to turn to England in search of decent opposition. They caused a stir in the first FA Cup, drawing 0-0 with the Royal Engineers in the semi-final, and only going out because they couldn’t afford to travel for the replay. It is often said that Queen’s Park revolutionised football with their passing and combination game, although there is also counter-evidence against the claim.

Queen’s Park would provide all eleven players in November 1872 for the first ever international against a selection of English players picked from the London clubs, plus Sheffield, Nottingham and Oxford University. Played in Glasgow and watched by 3,500 people, the game was as much about soccer versus rugby as it was about England versus Scotland. On the back of that success, soccer suddenly boomed in Scotland’s biggest city, to the extent that when the first Scottish FA Cup was played in 1875, it had 49 entrants compared to just 32 for the English one. Scottish teams would continue to enter the FA Cup through to 1887, but the relations became strained as candidly ‘professional’ teams in England plundered all the best Scottish talent, to the extent that the Scottish FA decided to ban its clubs from competing in England, which is why the countries still today have separate league and cup structures.

Queen’s Park would provide all eleven players in November 1872 for the first ever international against a selection of English players picked from the London clubs, plus Sheffield, Nottingham and Oxford University. Played in Glasgow and watched by 3,500 people, the game was as much about soccer versus rugby as it was about England versus Scotland. On the back of that success, soccer suddenly boomed in Scotland’s biggest city, to the extent that when the first Scottish FA Cup was played in 1875, it had 49 entrants compared to just 32 for the English one. Scottish teams would continue to enter the FA Cup through to 1887, but the relations became strained as candidly ‘professional’ teams in England plundered all the best Scottish talent, to the extent that the Scottish FA decided to ban its clubs from competing in England, which is why the countries still today have separate league and cup structures.

By 1872, Alcock was saying that “what has been the recreation of a few is now becoming the pursuit of thousands … almost magnified into a profession,” and by 1976, crowds of up to 20,000 people were attending matches. There were still problems with the rules, with the English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish FAs constantly making local modifications until 1886, when the International Football Association Board was formed to ensure that “no alterations in the laws of the game made by any association shall be valid until accepted by the board.” That body still oversees the laws of football today.

and by 1976, crowds of up to 20,000 people were attending matches. There were still problems with the rules, with the English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish FAs constantly making local modifications until 1886, when the International Football Association Board was formed to ensure that “no alterations in the laws of the game made by any association shall be valid until accepted by the board.” That body still oversees the laws of football today.

By this time, soccer was basically the same game as it is today. The few remaining changes included the Irish idea in 1891 of awarding penalty kicks to solve the constant problem of players stopping balls on the goal-line with their hands. Goal nets were introduced in 1892, goalkeepers were limited to handling the ball in their own area in 1915, the offside rule was modified to its current form in 1925, while injured players could not be replaced until 1958. Yellow and red cards didn’t come in until 1970, and since then, the only really major changes have been increases in the number of substitutions allowed and the banning of back-passes to the keeper in 1992.

It had been a rocky journey for the FA’s game, but ultimately it failed in its main objective. In 1863, its prime intention had been to create a new code for all football clubs to embrace. That never happened. Much of the country continued to play the game their own way, and the Football Association was going to face a tough rival. Although nowadays soccer and rugby are clearly very different games, in the 19th century the division was far less clear, and it was not at all certain which way the pendulum was going to swing.

Click here to buy the book and read the whole story.

24. SCRUM ON DOWN: The early days of Rugby Union

Leave a comment

Comments 0