17. Play For Today: British Shrovetide football

The authorities had won the battle, but not the war. Exactly forty years after football was banned in the city, Derby County FC was formed. There were few objections and the club is still going strong today. Treacle eating matches, to the best of our knowledge, are not.

In an earlier chapter, we learned how the centuries-old tradition of hurling has been maintained at St Columb in Cornwall. But this is just one of several examples in Britain of the custom of ‘mob football’ still existing today.

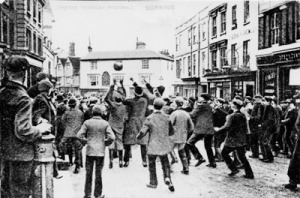

In most of these games, there are very few rules. Most of the action involves huge swathes  of people striving to advance the ball with any part of their bodies, plenty of cunning including attempts to conceal the ball, and tactics based on knowledge of the local geography. And ancient as these games might be, they have adapted with the times. Players wear modern clothes, not period costumes, and if any use exists for new technologies, from mopeds to mobile telephones, then somebody will probably try to find it.

of people striving to advance the ball with any part of their bodies, plenty of cunning including attempts to conceal the ball, and tactics based on knowledge of the local geography. And ancient as these games might be, they have adapted with the times. Players wear modern clothes, not period costumes, and if any use exists for new technologies, from mopeds to mobile telephones, then somebody will probably try to find it.

Right at the other end of the country from Cornwall, Kirkwall in the Orkneys still plays its ba’ game every Christmas and New Year. Tradition claims a Viking origin, although the earliest verifiable reference dates to a later period, 1684, when it was declared that when a couple married they had to “pay a foot-ball to the scholars of the grammour school.” Despite several demands, such as one in 1863 that “really it is high time that our citizens, young and middle aged, should bethink themselves of some more rational amusement,” the game survived all attempts to ban it in the 19th century, and is still played through the streets of Kirkwall by the Uppies and the Doonies today.

Folk football also survived well into the 20th century in several towns in the Scottish Borders region, and although less spectacular than the Kirkwall game, in some it is still played today. They say they once played the game with the heads of English invaders at Jedburgh, where the first known attempt to ban it was in 1704. But the prohibitions were ignored, and in 1849 a judge admitted that “I for one should hesitate to encourage the abolition of an old and customary game which from time immemorial has been enjoyed by the community.” In Duns, the game was last recorded in 1886, but was revived in 1949, and Denholm and Hobkirk valiantly maintain the tradition too. And so does Ancrum, thanks to the efforts of Iain Heard. Although in 1837 it was written of Ancrum that “there is no species of amusement to which the parishioners are especially attached, with the exception of the game of ball,” in 1974 the annual game was abandoned through lack of interest. Even if he had to play alone, Heard continued the tradition until 1997, when he finally managed to see it properly revived.

Folk football also survived well into the 20th century in several towns in the Scottish Borders region, and although less spectacular than the Kirkwall game, in some it is still played today. They say they once played the game with the heads of English invaders at Jedburgh, where the first known attempt to ban it was in 1704. But the prohibitions were ignored, and in 1849 a judge admitted that “I for one should hesitate to encourage the abolition of an old and customary game which from time immemorial has been enjoyed by the community.” In Duns, the game was last recorded in 1886, but was revived in 1949, and Denholm and Hobkirk valiantly maintain the tradition too. And so does Ancrum, thanks to the efforts of Iain Heard. Although in 1837 it was written of Ancrum that “there is no species of amusement to which the parishioners are especially attached, with the exception of the game of ball,” in 1974 the annual game was abandoned through lack of interest. Even if he had to play alone, Heard continued the tradition until 1997, when he finally managed to see it properly revived.

Royal Shrovetide at Ashbourne is probably England’s most celebrated folk football tradition. There are unsubstantiated claims that it dates back to the 12th century, but all we can say for certain is that in 1821 it was sung that “Shrove Tuesday, you know, is always the day, when the pancake’s the prelude and the football’s the play.” Like in so many English towns in the 19th century, the authorities sought to have the game banished from the streets, but Ashbourne was one of the few places where the locals managed to stand their ground. Following a drowning in 1878, it was felt the custom “has been observed for the last time,” but that was not so. The following years brought violent confrontations with the police and as it was said in 1920, “organised opposition had the effect of giving to the ancient game a new lease of life.” The whole town still goes wild for the game played every year on Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday, and now receives plenty of media coverage and has become a popular tourist attraction.

Most of the claims to antiquity of these traditions are questionable at best, and there is no real proof that Atherstone’s game dates back 800 years to the time of King John, but it certainly existed in 1790 and like in Ashbourne survived several sometimes brutal 19th century attempts to ban it.

Most of the claims to antiquity of these traditions are questionable at best, and there is no real proof that Atherstone’s game dates back 800 years to the time of King John, but it certainly existed in 1790 and like in Ashbourne survived several sometimes brutal 19th century attempts to ban it.

And at Sedgefield in County Durham, they say the game dates back to one between farmers and the builders of the local church in the 13th century, although there are no real records of it being played any earlier than 1802.

Workington is the largest town in Britain that still plays mob football, and is probably the toughest variant of all. A game was watched by 2,000 people in 1775, when it was already being described as an ancient custom, and one of the reasons for its survival is an expanse of fields, rivers, bridges and hillocks called the Cloffolks, where the game could be played without causing any particular worry to fellow citizens and it doesn’t seem to have ever had to face any attempted prohibitions.

Two of the surviving games don’t involve a ball at all. In Leicestershire, the exceedingly violent cross-country tradition of Easter Monday bottle kicking involves the people of Hallaton and Medbourne battling to get a small barrel back to their respective villages. And in Lincolnshire, the Haxey Hood, dating back to at least 1815, is all about huge crowds ‘swaying’ to get a tube containing a length of rope into their chosen pub.

Two of the surviving games don’t involve a ball at all. In Leicestershire, the exceedingly violent cross-country tradition of Easter Monday bottle kicking involves the people of Hallaton and Medbourne battling to get a small barrel back to their respective villages. And in Lincolnshire, the Haxey Hood, dating back to at least 1815, is all about huge crowds ‘swaying’ to get a tube containing a length of rope into their chosen pub.

These are the game that survived, and some are in better health than others, but many similar traditions have disappeared. Derby once held one of the most celebrated games of all, where in 1791 William Hutton marvelled at how “I have seen a foot-ball hero chaired through the streets like a successful Member, although his utmost elevation of character as no more than that of a butcher’s apprentice.” However, in 1832 it was written that “it is not a trifling consideration that a suspension of business for nearly two days should be created for the inhabitants for the mere gratification of a sport once so useless and barbarous,” and twenty years later, opposition to the game eventually saw it outlawed for good.

The Highway Acts of 1830 are largely to blame for the tradition’s disappearance. With more and more transport on the roads, there was a need to establish legislation. The Acts did not have any particular problem with football or other such entertainments, but did want to stop people from having that fun in the middle of the road. And particularly thanks to the establishment of Britain’s first organised police force around the same time, when people were told that they couldn’t play ball games in a certain place, there was finally a reliable system in place to ensure they did as they were instructed.

The Highway Acts of 1830 are largely to blame for the tradition’s disappearance. With more and more transport on the roads, there was a need to establish legislation. The Acts did not have any particular problem with football or other such entertainments, but did want to stop people from having that fun in the middle of the road. And particularly thanks to the establishment of Britain’s first organised police force around the same time, when people were told that they couldn’t play ball games in a certain place, there was finally a reliable system in place to ensure they did as they were instructed.

At Twickenham, at Kingston, at Nuneaton, at Dorking and many other places, the common people lost the battle to maintain the street football tradition. Such comments as one in Liverpool in 1831 that “a spirit has lately arisen in the land … to curb, restrain and almost completely forbid the lowly, the humble of society from indulging in any pastimes whatsoever” have been used to support the theory that the prohibitions were the cause for football’s demise, but it was mob football in the street rather than organised games in fields that these bans focused on. As the Common Law of Scotland stated in 1832, football and other sports “when the purposes of the meeting are not public disturbances or the accomplishment of any violent and illegal objects, do not fall under the offence of mobbing or rioting.”

At Twickenham and Derby, for instance, the local council banned the annual street match but offered cash prizes for football games in fields and parks. The same happened at Alnwick in Northumberland, where ‘scoring the hales’ dates back to at least 1788, when “a foot-ball was thrown over the castle-walls to the populace.” In 1828, it faced an attempt to see it outlawed, but the Duke of Northumberland agreed to give the winning side five sovereigns provided they played in the pastures and not the town centre. Such attempts at bribery were scorned in other places, but not in Alnwick, and the tradition continues, although not in the streets.

At Twickenham and Derby, for instance, the local council banned the annual street match but offered cash prizes for football games in fields and parks. The same happened at Alnwick in Northumberland, where ‘scoring the hales’ dates back to at least 1788, when “a foot-ball was thrown over the castle-walls to the populace.” In 1828, it faced an attempt to see it outlawed, but the Duke of Northumberland agreed to give the winning side five sovereigns provided they played in the pastures and not the town centre. Such attempts at bribery were scorned in other places, but not in Alnwick, and the tradition continues, although not in the streets.

It would therefore seem that this was the era when large-scale mob games gave way to more structured games within smaller and clearly defined boundaries. But a comment made in Derby in 1830 suggests otherwise, for the writer felt that street football in which the ball was carried rather than kicked “originated from the regular game of foot-ball, and that the alteration in the mode of play [was caused] as the line of road to either goal became more thickly studded by buildings, the danger of breaking windows, etc, dictated the adoption of the present method.”

It would therefore seem that this was the era when large-scale mob games gave way to more structured games within smaller and clearly defined boundaries. But a comment made in Derby in 1830 suggests otherwise, for the writer felt that street football in which the ball was carried rather than kicked “originated from the regular game of foot-ball, and that the alteration in the mode of play [was caused] as the line of road to either goal became more thickly studded by buildings, the danger of breaking windows, etc, dictated the adoption of the present method.”

We know that football as described by Francis Willoughby had existed since the 1600s, and mob football may have really been something that mushroomed out of that, rather than the other way round. Evolutionary logic suggests that might be the case, but by the 1800s, these massive festive gatherings had gotten so out of control that the authorities felt it was time something was done about it. Ordinary small-scale football in the fields, although going somewhat out of fashion, was never really a problem.

Click here to buy the book and read the whole story.

18. HIGH SCHOOL BALLS: Early football in British public schools

Leave a comment

Comments 0